When One Core Wasn’t Enough: Why Systems Got More Complex

When I first started learning about distributed systems and concurrency, I kept thinking: why are we talking about multiprocessors? Honestly, I didn’t know what most of the big words meant yet. Locks, CAS, linearizability, consensus. I just knew I wanted to understand how real systems behave when many things run at the same time.

But the more I went through it, the more I realized: multiprocessors are the reason ALL of those topics exist.

If you understand the “multiprocessor problem”, the rest of the course becomes logical instead of random.

What helped me understand it was the simple reason parallel computing became necessary in the first place. For a long time, CPUs were getting faster so quickly that you could almost wait for the next generation and your program would run faster. The rough story I kept seeing was that from 1986 to 2002 single-processor performance was growing around 50 percent per year, then after that it slowed down closer to 20 percent per year. That is still growth, but it is not the same world. And the bigger shift was that hardware progress started to come more from adding cores, not from making one core dramatically faster.

So I start here because it answers a basic question. If computers have multiple cores now, why do we not automatically get faster software?

The world is multiprocessor by default now

Earlier intuition (single CPU):

- You write code.

- It runs step-by-step.

- If it’s slow, you optimize the algorithm or the code.

New reality (multi-core / multi-thread):

- Your laptop already runs many things at once.

- Servers run thousands of requests at once.

- Even a “single app” is usually multiple threads (runtime, GC, async tasks, background jobs).

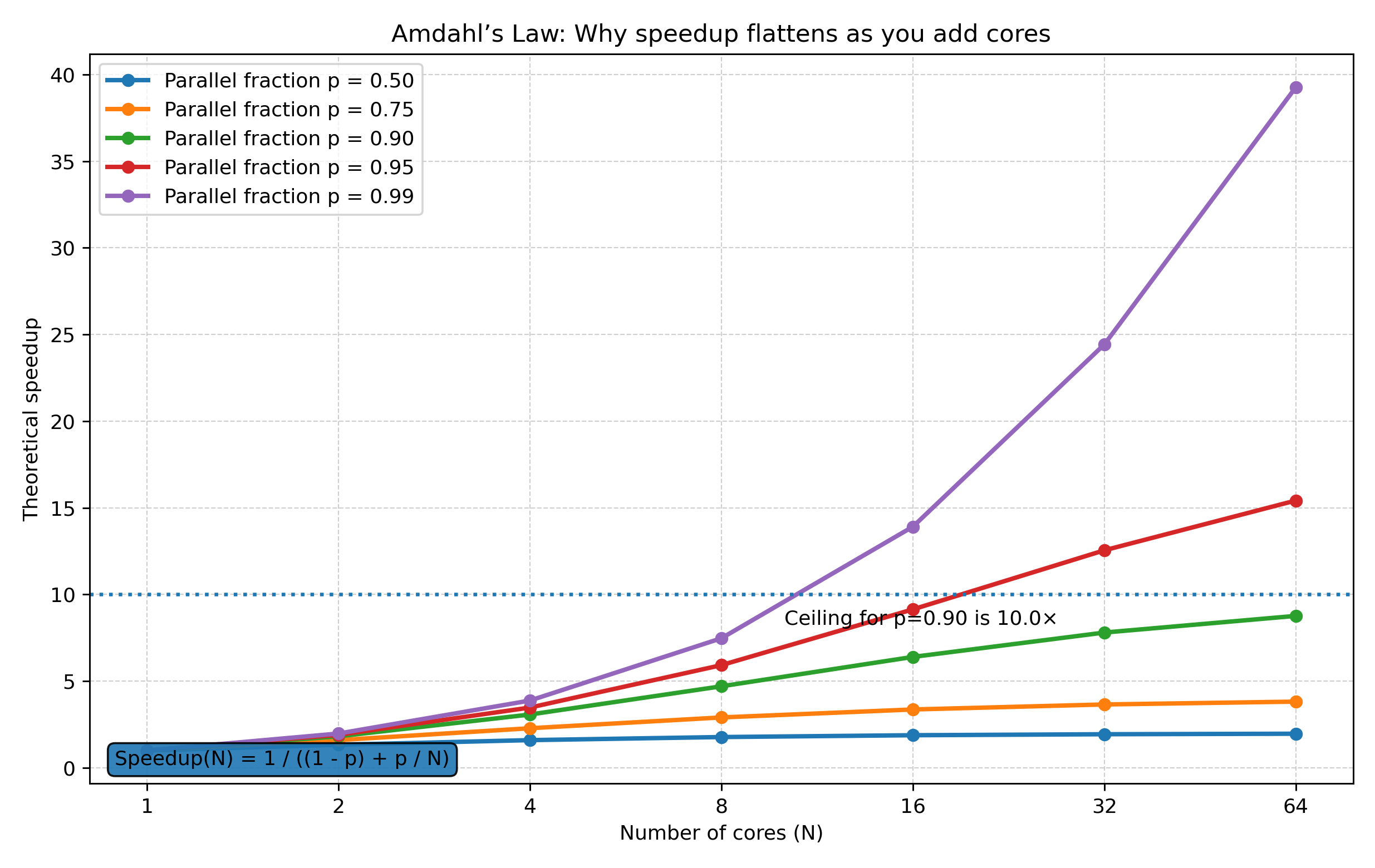

This is also where the first painful lesson shows up. Even if you add more cores, you do not automatically get 10x speed.

So the real question becomes: What fraction of this work can actually run in parallel, and what fraction is forced to be sequential?

Why we still want more performance

One thing I liked is that the motivation was not only “make apps faster.” It was more like, some problems are literally not practical without more compute. The early examples were things like climate modelling, protein folding, drug discovery, energy research, and large-scale data analysis. As computation grows, we attempt bigger and more detailed versions of these problems. So the demand grows with the supply.

So this is where concurrency starts to matter. Once hardware moved to multicore, we needed a different software style that actually matches how the hardware runs. Instead of one straight-line flow, we needed software that can split work safely, coordinate it, and still stay correct.

Multiprocessors create two problems at the same time

Before even talking about software, there is a hardware reason this happened. For decades, performance gains came from packing more transistors and pushing clock speeds. But as transistors got smaller and clocks went up, power usage and heat also went up. At some point you cannot just keep making a single core faster because the chip gets too hot and becomes unreliable. So the industry pivoted.

This is also exactly where Amdahl’s Law becomes relevant. Once CPUs became multicore, “just add more cores” sounded like a free speed boost. But Amdahl’s Law says speedup is limited by the part of the program that is still sequential. Even with unlimited cores, the sequential part never disappears, so the curve always flattens.

Instead of one very fast core, we started getting multiple cores on one chip. That is where “multicore” became normal.

Problem A: Speed (parallelism)

We want things faster by splitting work across cores.

Example idea:

- Sum an array: split into chunks, each core sums a chunk, then combine.

Sounds easy… but the catch is: speedup is not free.

Why?

- You pay overhead: creating threads, merging results, scheduling.

- You hit bottlenecks: shared memory traffic, shared locks, shared hot spots.

- Sometimes your “parallel version” becomes slower.

So the key takeaway is: parallel time depends on both the algorithm and the coordination cost.

Problem B: Correctness (interference)

This is the bigger one.

When multiple processors touch the same shared data:

- operations overlap

- reads and writes interleave

- the result can become incorrect even if your logic was “correct” in single-thread thinking

This is where bugs come from that are:

- random

- hard to reproduce

- only happen under load

This is also where another lesson shows up. Having multiple cores does not help if your program is still written like a single-thread program. Running multiple copies of the same program on different cores is usually not what we want. We want one program to finish faster. That means we have to rewrite parts of it to be parallel.

People always ask, why not just have a compiler that automatically converts serial code to parallel code? The honest answer is that it is really hard to do well. Even if a tool recognizes patterns, it can generate parallel code that is inefficient because of coordination overhead. A classic example is matrix multiplication. You can express it as lots of dot products, but turning that into tons of tiny parallel tasks can be slower on real systems. So in practice, we still need humans to design parallel algorithms and control how the parallel work is structured.

This is why the next topics matter:

- linearizability (what does “correct” even mean under overlap?)

- progress properties (does the system keep moving?)

- consensus/fault tolerance (agreement under failures)

But those topics are basically responses to the core multiprocessor reality.

Why simplified models help

Real machines have details that are hard to reason about directly:

- caches and cache coherence

- contention on memory and shared data

- different costs for “the same” memory access

- scheduler effects that add noise

So when you want to understand the core idea of a parallel algorithm, it helps to start with a simplified model (PRAM is a common one). It strips away hardware-specific behaviour and lets you focus on the main questions:

- In an ideal setting, what is the best parallel time we can hope for?

- How many processors does that time require?

- What is the tradeoff between time and total work?

For me, this is useful because it separates two things. First, what the algorithm can do in principle. Second, what real machines might prevent you from reaching.

Key tradeoff: Time vs processors (and total work)

You can often reduce time by throwing more processors at the problem, but you might waste ridiculous total work.

What this means in practice:

- “O(1) time” can be possible if you use an insane number of processors

- but then the total work becomes huge and unrealistic

So you learn to think like:

- How fast? (parallel time)

- At what cost? (processors, work, contention)

How this changed how I think

I used to think multicore just means “my code runs faster.” Now I look at it differently.

First, I ask what part of the work can truly run in parallel, and what part is still forced to be sequential. Then I ask what it costs to coordinate the parallel parts, because coordination can easily cancel the benefit.

And the last big change is how I see shared memory. It is not just a shared place to store data. It is also a shared place where threads collide, and where bugs show up if you don’t control the timing.

That’s why I start with multiprocessors. If you don’t get the “why” here, the rest feels like random terminology.

The short version is: We could not keep making one core faster, so we added more cores. But more cores bring new limits. Some work still has to be done one-after-another, and a lot of time gets burned on coordination.

Once you see that, ideas like correctness and progress make more sense. They are basically the rules we use to make sure parallel code does not break or get stuck.

Conclusion

This is why I start with multiprocessors. It sets the context for everything else. At some point, making a single core faster stopped being the easy path, so hardware shifted to multiple cores. After that, software also had to change.

When you try to use many cores, two issues show up right away. First, speedup has a limit. Some parts still run sequentially, and coordination takes time. Second, shared state becomes risky. If multiple threads touch the same data without a plan, you get bugs that are hard to reproduce.

That is why topics like correctness and progress matter. They are not “extra theory”. They also carry directly into distributed systems. A distributed system replaces shared memory with message passing, but the core challenges stay similar: coordination, consistency around shared state, timing uncertainty, and keeping the system correct under load and faults.

Sources

- Pacheco, Peter S. and Malensek, Matthew. An Introduction to Parallel Programming (Chapter 1: “Why Parallel Computing?”).

- “Amdahl’s law” (definition and speedup formula), Wikipedia.